International law in the Mekong region is a complex and multifaceted topic, given the diversity of countries, interests, and challenges present in this geographical area. The Mekong region is shared by 6 countries (China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam), each with its own laws and institutions.

By Federica Masellis

Introduction

Three-quarters of the world’s rivers flow through more than one country. 40% of the world’s population lives in transboundary river basins. International rivers are “open to all states on terms of complete equality”; no nation can claim sovereignty of international rivers. International law, however, also gives riparian states significant rights to access international rivers, provided they act reasonably. “Reasonable use” is a core legal doctrine and, therefore, central to understanding how international law should govern the allocation of international rivers between the nations whose territories are drained.

The purpose of this paper is to understand the ways in which international law impacts disputes over the construction and operation of hydropower dams on the Mekong River and if the cooperation on Mekong is functional. The paper begins with a brief background of the Mekong River and the dams’ construction. Then an analysis of international law as it should operate in the context of international rivers, and it proceeds on the analysis of the legal justification and position of the riparian states.

Background of the Mekong River And Dams

The Mekong River – known as the Lancang River in Chinese – originates in China, and then flows 4,200 km through Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia where it empties into the South China Sea. It gives life to an estimated seventy million people [1].

With the economic and social development of the riparian countries, the demand for water has increased, causing disputes mainly due to a significant expansion of dam construction for hydropower by China. As of 2024 (Figure 1), there are 12 operational dams on the Lancang in China alone [2], Cambodia has revealed plans for 2 mainstream dams and Laos has planned 9 dams with 2 already operational [3].

At present, downstream countries fear negative impacts such as increased flooding and seasonal water shortages and it is estimated that these numerous dams could reduce fish availability by 40 percent by 2030 [4]. Up until now, the approach of these disputes has been negotiated on a case-by-case basis through diplomatic means and international mechanisms [5].

Politics Perspective on Cooperation

Cooperation among riparian states on transboundary river water management is essential but challenging due to international politics. Stronger upstream nations, like China, often avoid cooperation, leveraging their power to secure compliance from weaker states without force, reflecting a realist view of international relations as power-driven and distrustful [6]. Conversely, neoliberal institutionalism emphasizes cooperation, especially important with climate change and freshwater scarcity. This perspective suggests states rationally prefer cooperation over conflict, supported by treaties and river basin organizations that prevent disputes by defining rights and responsibilities [7].

Effective institutions need clear rules, conflict-resolution mechanisms, decision-making authorities, and flexible management structures. Cooperation is difficult without clearly defined terms. For example, China’s water-related agreements with its neighbours typically include clauses on their applicability in terms of ratione loci and ratione materiae. Equitable benefit-sharing among stakeholders is also crucial for sustained cooperation [8].

History of Mekong Cooperation until 1995

Cross-border cooperation in the Mekong Basin began after World War II, when the United States established the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (ECAFE) to help Southeast Asia. The first major move towards formal cooperation was the so-called “March 17 Agreement” in 1957 between Thailand and Laos. A committee was formed to support hydropower and irrigation projects. At that time China was not internationally recognized and Myanmar did not join [9]. The Mekong Secretariat, created later, focused on technical analysis. The United States, France and Japan supported the committee in the 1960s, promoting regional cooperation for peace. Interest waned in the 1970s due to the end of the Vietnam War and the civil war in Cambodia, leading to an “Interim Committee” in 1978. In 1987, the Indicative Basin Plan shifted to national projects with environmental considerations. The committee maintained its status as an interim committee until the establishment of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) in 1995 with the Mekong Agreement [10].

Legal Framework

International law governing transboundary rivers is based on principles of “equitable use” and “no significant harm”, mainly influenced by the Harmon Doctrine and customary international law [11].

Historically, key treaties such as the Treaty on the River Plate Basin (1969)[12], the Helsinki Rules (1967)[13], Mekong Agreement (1995)[14], UNECE Water Convention (1992)[15] and the UN Watercourses Convention (1997)[16] reflect these principles through provisions for equitable utilization, prevention of transboundary impact, sustainable management, and joint management. Common across these treaties are indeed the principles of equitable and reasonable utilization of water resources, cooperation through joint institutions and data sharing, environmental protection, and mechanisms for peaceful dispute resolution [17].

Generally, lower riparian states focus on preventing harm from upstream activities, while upper riparians seek fair usage rights for their development needs. This framework supports resource management through cooperation, environmental protection, and socio-economic development, while also addressing dispute prevention and resolution [18].

Mekong multilateral regional governance bodies

A transnational area of such significant socioeconomic, environmental and cultural interest has seen a succession of various attempts at multilateral governance over time, which have had and continue to have considerable difficulty in achieving results that bring real benefits to all partners in a balanced way [19].

Mekong River Commission (MRC)

The Mekong River Commission (MRC) is a multilateral body formed by Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam who signed a ‘Cooperation Agreement for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin’ (1995 Mekong River Agreement) in Chiang Rai (Thailand) on 5 April 1995 [20].

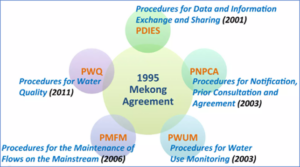

One of the main objectives of this instrument is to achieve “the full potential of sustainable benefits to all riparian countries and the prevention of wasteful use of Mekong River Basin waters”[21]. The instrument promotes sustainable development through Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) and cooperation among Mekong Basin countries. It aligns with international treaties like the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (UNWC) and mandates compliance with the 1992 Rio Declaration’s principles. It requires Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (EIA and SIA) for large projects that ensures balanced development and environmental protection. It manages the basin sustainably, collecting and sharing data, monitoring ecological health, coordinating water resource management, and mediating conflicts. It has a comprehensive procedures framework for managing the basin (Figure 2) [22].

It is important to note that the MRC struggles to resolve rising tensions due to the lack of enforcement powers and the fact that China and Myanmar participate only as observers and dialogue partners under the Agreement [23].

Lancang – Mekong Cooperation (LMC)

In 2012, Thailand proposed a sustainable development initiative for the entire Mekong basin, including the Chinese section, which was favorably received by China. At the China-ASEAN summit in 2014, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang presented the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Framework. In March 2016, leaders of the six countries met in Sanya, Hainan, and signed the Sanya Declaration, officially launching the LMC with the “3+5” cooperation model: three pillars (politics and security, economy and society, sustainable development) and five priorities (connectivity, production capacity, cross-border economic cooperation, water resources, agriculture and poverty alleviation) [24].

Short of joining the LMC, downstream countries have no practical leverage over China. Beijing can use sovereignty as a shield to fend off external concerns about dam construction and related water issues from other Mekong River-focused organizations and agreements, as well as from individual riparian countries. The huge military capability gap between China and other Mekong countries makes violent options impractical [25]. The LMC presents also challenges for China. China could be blamed for Mekong water disasters, impacting its credibility. The LMC limits China’s ability to use dams as a political tool, as unilateral actions to regulate water flows become impractical if Beijing wants to sustain the organization’s importance [26].

Others

Other multilateral regional governance bodies:

- Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program [27]

- Cambodia-Lao PDR-Viet Nam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA) [28]

- Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI) [29]

- Mekong – U.S. Partnership [30]

- Friends of the Lower Mekong (FLM) [31]

- Mekong-Ganga Cooperation (MGC) [32]

- Mekong-Japan Cooperation [33]

Key Actors

China

China has signed several important global agreements on river use at the international level. Some notable examples are the 1997 United Nations Convention on Watercourses (drafted but not ratified, this allows it to avoid obligations that would limit its sovereignty), the Helsinki Rules (1966), and the Berlin Rules (2004), which promote equitable and sustainable water use [34].

China’s stance on the affairs of transboundary waterways is to use mainly international diplomacy, defined as the “soft path” of cooperation that underlies Chinese foreign policy. This approach, based on dialogue, consultation and peaceful negotiation, has been expressed in legal doctrine and confirmed in President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy statements [35]. This is evident from his ambitious mega-digit projects on the Lancang, which he considers national projects. Based on this assumption, the country considers these projects exempted from international law, particularly prior consultation with MRC member states, and it assumes no obligation to refrain from causing significant harm to these states. But, at the same time, China is a dialogue partner in the Mekong River Commission (MRC) and member of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), demonstrating an openness to regional dialogue and cooperation [36]. Moreover, China’s projects, such as the Xayaburi, Don Sahong, Pak Beng and Sanakham dams, are designed with “run-off-the-river”[37] configurations in line with China’s strategy of maximizing renewable energy production.

In addition to its interest in hydropower generation, China plans to make parts of the Mekong wider and deeper to accommodate larger vessels and increase trade along the river. China wants to use ships capable of carrying 500 tons of goods (now they carry 100), from Yunnan Province to Luang Prabang, Laos. This would mean blasting rocks and dredging the rapids in a narrow part of the river[38].

Overall, the Chinese perspective on Mekong River hydropower projects revolves around national development priorities and the use of natural resources to support economic growth, while recognizing the need for regional cooperation and management to effectively address common concerns.

Vietnam

Vietnam is a strong advocate of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, which it has ratified in 2014 with a reservation: “The Socialist Republic of Viet Nam reserves the right to choose the appropriate means of dispute settlement notwithstanding the decision of the other party to the concerned dispute” [39]. It is also a full member of the MRC, and it participates in the LMC. Vietnam frequently invokes the principles of international watercourses law in its diplomatic communications and negotiations to try to ensure prior notification and consultation on upstream projects that could impact downstream countries. It also promotes cooperation and sustainable management of the Mekong River through the MRC and LMC [40].

At the national level, Vietnam has pursued its own dam projects to support economic development, with legal discussions focusing on investor obligations and compliance with safety and environmental standards. The Ministry of Industry and Trade and other state agencies evaluate hydropower projects to ensure that they meet necessary discharge requirements during droughts and ensure the safety of downstream dams during floods [41].

Overall, Vietnam’s position on the Lancang-Mekong is shaped by a strong adherence to international watercourse law, emphasizing equitable and sustainable use of the river’s resources. Through its active participation in the MRC and advocacy for the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, Vietnam strives to uphold international norms in its bilateral and regional interactions. However, the effectiveness of these efforts is constrained by the differing priorities and sovereignty claims of upstream countries like China.

Myanmar

Among the Mekong countries, Myanmar is the only one that does not border China. This geographic location makes Myanmar less susceptible to China’s use of water as an instrument of pressure [42].

As framework, Myanmar is only a dialogue partner to the MRC, like China, but it’s a full member of the LMC. Moreover, it supported, but not ratified the 1997 United Nations Convention on Watercourses. The country aims to develop hydropower to meet energy demand and boost economic growth. It has launched several dams’ projects with domestic and international investors. Its legal framework requires rigorous environmental and social impact assessments, aligning with international standards. The Ministry of Agriculture oversees these projects, ensuring compliance with legal obligations and sustainability criteria. Myanmar has practiced a policy of gradually reducing the conventional use of water resources from the Mekong and Chiao Lan rivers for small-scale power generation and local irrigation, thus avoiding conflicts over river flow variations [43].

Overall, Myanmar’s position on the Mekong River is shaped by a complex interplay of international legal principles, regional dynamics, and national development priorities. The country’s efforts to address these challenges reflect a commitment to sustainable and equitable management of water resources in the Mekong Basin.

Laos

A small, landlocked country in Southeast Asia, Laos relies on fishing, agriculture, and forestry for income but aims to boost its economy through hydropower, aspiring to become the “battery” of Southeast Asia. Over the past 15 years, Laos has built over 50 dams and has another 50 under construction, prioritizing profit despite exceeding electricity demand and raising environmental and social concerns [44].

Laos is an active member of the Mekong River Commission (MRC), participates in regional consultation and notification mechanisms. The country adheres to the principles outlined in various international agreements, including the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which, although signed, is not yet ratified by Laos. Despite this cooperation, Laos often proceeds with hydropower projects, such as the Xayaburi Dam (build with a Thai Company), even amidst environmental concerns from downstream countries like Cambodia and Vietnam. The most recent seventh large dam, Sanakham Dam, will be built with the assistance of a Chinese company. These projects frequently lack proper notification and impact assessments, leading to legal disputes [45].

In the event of disputes, Laos advocates for negotiation, consultation, or mediation to resolve issues amicably. The country emphasizes goodwill, understanding, and trust to find lasting solutions, reinforcing the role of international agreements and organizations in preserving regional stability and promoting socio-economic development. Laos’ legal frameworks for hydropower projects involve rigorous assessments by relevant state agencies to ensure compliance with environmental and social standards. These frameworks are designed to minimize transboundary impacts and align with the MRC’s cooperative guidelines [46].

Thailand

Thailand, one of the most populous and economically developed countries in the Mekong region, plays a crucial role in managing the Mekong River, adhering to principles of international law as outlined in the 1995 Mekong Agreement. Although Thailand has not ratified the 1997 United Nations Convention, it supports principles of fair and reasonable utilization and the duty to cooperate with other Mekong States [47].

Despite challenges posed by dam construction upstream by countries like China, Thailand promotes transparency and data sharing, striving to adhere to principles of notification and prior consultation for activities with significant transboundary impacts. However, adherence to these principles has not always been respected, as evidenced by the case of the Xayaburi Dam in Laos. The country benefits from hydroelectric energy produced by dams in Laos, yet this raises internal controversies concerning the balance between energy needs and environmental protection [48].

Through the Mekong River Commission (MRC), Thailand seeks to foster regional cooperation and sustainable river management, committing to uphold international legal frameworks and balance its development needs with environmental impacts on other countries. Thailand’s domestic policies reflect these commitments, incorporating environmental impact assessments and public consultations to ensure the sustainability of Mekong-related projects [49].

In conclusion, Thailand continues to navigate the challenges of Mekong management through regional cooperation, respect for principles of international law, and the adoption of sustainable domestic policies, while addressing the complexities of disputes related to transboundary water resource management.

Cambodia

As a country located downstream, Cambodia is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of upstream activities. This vulnerability underscores Cambodia’s dependence on international legal frameworks. Cambodia actively participates in the Mekong River Commission (MRC), working with other member states to ensure sustainable and cooperative management of the Mekong River. Through the MRC, Cambodia emphasizes the need for upstream countries to provide advance notification and consultation for projects that could have significant transboundary impacts, reflecting the international legal principle of cooperative water management [50].

Domestically, Cambodia has developed policies that include environmental impact assessments and public consultations for projects that affect the Mekong. These policies are designed to comply with both domestic regulations and international legal standards, reinforcing Cambodia’s commitment to responsible management of the river [51].

A prominent case in point is the Sambor Dam, which is the subject of intense discussion in Cambodia. Originally proposed by China Southern Power Grid Company to be built in the town of Sambor, it would have been the largest hydroelectric dam in the Mekong River basin, with a size larger than any other dam there. A feasibility study conducted by the National Heritage Institute found that the dam would completely block fish migration and significantly reduce the flow of sediment and nutrients to the Mekong Delta, making the latter unsustainable. In 2011, China Southern Power Grid Company withdrew from the project citing corporate responsibility. However, the Cambodian government later collaborated with the China Guodian Corporation on a feasibility study on the dam. In 2017, Prime Minister Hun Sen announced a moratorium on new dams in the Mekong, which was extended into 2020, keeping the construction of the Sambor Dam uncertain. Environmental and social concerns, including impacts on fish migration and the river ecosystem, have prompted environmental organizations and local communities to oppose the project. At present, the Sambor Dam has not been built and the Cambodian government continues to assess the impacts of hydropower projects on the Mekong River and affected communities [52].

In summary, Cambodia’s position on the Lancang-Mekong River is heavily influenced by international law, which guides its multilateral and bilateral commitments as well as domestic policies. By promoting the equitable and sustainable use of the Mekong’s resources, Cambodia seeks to protect its development goals while ensuring the river’s ecological integrity and supporting the livelihoods of its people.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to understand the impact of international law on disputes over the construction and operation of hydropower dams on the Mekong River and to evaluate the functionality of cooperation mechanisms. The analysis reveals that while international legal frameworks, such as the 1995 Mekong Agreement, provide a foundation for cooperation and conflict resolution, their effectiveness is undermined by weak enforcement and varying national interests. The lower riparian states often blame China for the Mekong’s problems, yet all states contribute to the challenges due to their respective priorities and actions.

The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation emerges as a promising model for future collaboration, as it includes all riparian states and establishes clear rights and obligations. For this cooperation to be functional and effective, it must overcome enforcement challenges and ensure that all member states are committed to equitable and sustainable management of the Mekong River. Strengthening this cooperation framework is essential for addressing the complex socio-economic and environmental issues surrounding hydropower development on the Mekong.

Note

[1] Le-Huu Ti et al., Mekong Case Study, UNESCO (France, 2003).

[2] “Sites of Struggle and Sacrifice: Mapping Destructive Dam Projects along the Mekong River,” 2024, last accessed 04/07/2024, https://www.internationalrivers.org/news/sites-of-struggle-sacrifice-mapping-destructive-dam-projects-along-the-mekong-river/.

[3] Maria Stern and Joakim Öjendal, “Exploring the security-development nexus,” The security-development nexus (2012).

[4] Andrea Natalini, “Mekong area: geopolitical, economical, environmental and humanitarian problems,” IRIAD Review, no. 8 (August 2022).

[5] Susanne Schmeier, “The role of institutionalized cooperation in transboundary basins in mitigating conflict potential over hydropower dams,” Frontiers in Climate 5 (2024).

[6] Selina Ho, “Introduction to ‘transboundary river cooperation: actors, strategies and impact’,” Water International 42, no. 2 (February 2017).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Patricia Wouters and Huiping Chen, “China’s ‘soft-path’to transboundary water cooperation examined in the light of two UN global water conventions–exploring the ‘Chinese way’,” (2013).

[9] Jeffrey W. Jacobs, “The Mekong River Commission: transboundary water resources planning and regional security,” Geographical Journal 168, no. 4 (2002).

[10] Jörn Dosch, “Toward a new Pax Sinica? Relations between China and Southeast Asia in the early 21st Century,” México y la Cuenca del Pacífico, no. 34 (2009).

[11] Joseph W. Dellapenna, “The customary international law of transboundary fresh waters,” International journal of global environmental issues 1, no. 3-4 (2001).

[12] This treaty was among the earliest to reflect principles of equitable utilization and prevention of transboundary impact.

[13] Although not legally binding, these rules codified state practices regarding non-navigational river uses, influencing subsequent agreements and projects.

[14] Provides a legal framework for water use and sustainable development in the Mekong River Basin, emphasizing environmental principles and integrated water resources management.

[15] Focuses on transboundary water management, including principles of cooperation, sustainable management, and dispute resolution.

[16] Sets out principles for equitable and reasonable utilization of shared watercourses, prevention of significant harm, and mechanisms for cooperation and dispute resolution.

[17] Dellapenna, “The customary international law of transboundary fresh waters.”

[18] Ibid.

[19] Natalini, “Mekong area: geopolitical, economical, environmental and humanitarian problems.”

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Mekong Agreement “, (1995). Art.2

[22] Patricia Wouters, “International Law – Facilitating Transboundary Water Cooperation,” Published by the Global Water Partnership, TEC Background Papers, no. 17 (2013).

[23] Dosch, “Toward a new Pax Sinica? Relations between China and Southeast Asia in the early 21st Century.”

[24] Natalini, “Mekong area: geopolitical, economical, environmental and humanitarian problems.”

[25] “The Trouble with the Lancang Mekong Cooperation Forum,” 2018, last accessed 05/07/2024, https://thediplomat.com/2018/12/the-trouble-with-the-lancang-mekong-cooperation-forum/.

[26] Wu, “The Trouble with the Lancang Mekong Cooperation Forum.”

[27] Natalini, “Mekong area: geopolitical, economical, environmental and humanitarian problems.”

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Natalini, “Mekong area: geopolitical, economical, environmental and humanitarian problems.”

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] James D. Fry and Agnes Chong, “International Water Law and China’s Management of Its International Rivers,” BC Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 39 (2016).

[35] Wouters and Chen, “China’s ‘soft-path’to transboundary water cooperation examined in the light of two UN global water conventions–exploring the ‘Chinese way’.”

[36] Selina Ho, “River politics: China’s policies in the Mekong and the Brahmaputra in comparative perspective,” Journal of Contemporary China 23, no. 85 (2014).

[37] The “run-of-the-river” configuration for dams generates electricity by diverting a portion of a river’s natural flow through turbines without significantly altering the river’s flow or creating large reservoirs.

[38] Michael Sullivan, “China reshapes the vital Mekong River to power its expansion,” National Public Radio (2018).

[39] United Nations, “Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses,” (1997).

[40] Priyanka Mallick, “Transboundary River Cooperation in Mekong Basin: A Sub-regional Perspective,” Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs 9, no. 1 (2022).

[41] Nga Dao, “Dam development in Vietnam: The evolution of dam-induced resettlement policy,” Water Alternatives 3, no. 2 (2010).

[42] Victor Konrad and Zhiding Hu, “Expanded border imaginaries and aligned border narratives: ethnic minorities and localities in China’s border encounters with Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam,” in Border images, border narratives (Manchester University Press, 2021). [43] Shaofeng Jia et al., “Basin Governance and International Cooperation,” Deliang Chen Junguo Liu (2024).

[44] “Why is Laos building Mekong dams it doesn’t need?,” 2021, last accessed 04/07/2024, https://www.dw.com/en/why-is-laos-building-mekong-dams-it-doesnt-need/a-56231448.

[45] Mallick, “Transboundary River Cooperation in Mekong Basin: A Sub-regional Perspective.”

[46] Natalini, “Mekong area: geopolitical, economical, environmental and humanitarian problems.”

[47] Chris Sneddon and Coleen Fox, “Rethinking transboundary waters: A critical hydropolitics of the Mekong basin,” Political geography 25, no. 2 (2006).

[48] Gabriele Giovannini, “Power and geopolitics along the Mekong: The Laos–Vietnam negotiation on the Xayaburi dam,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 37, no. 2 (2018).

[49] Anoulak Kittikhoun and Denise M. Staubli, “Water diplomacy and conflict management in the Mekong: From rivalries to cooperation,” Journal of Hydrology 567 (2018).

[50] Kittikhoun and Staubli, “Water diplomacy and conflict management in the Mekong: From rivalries to cooperation.”

[51] Ung Phyrun, “The environmental situation in Cambodia, policy and instructions,” Biopolitics, the bio-environment, and bio-culture in the next millennium 5, no. 9 (1996).

[52] Lynn Phan, “The Sambor dam: how China’s breach of customary international law will affect the future of the Mekong River Basin,” Geo. Envtl. L. Rev. 32 (2019).

Photo: Mekong river